The Dorito Effect

Why fortune favours the bold for Clapham restaurants

“Where’s the best place to eat in Clapham?” I was recently asked by a friend who had taken the plunge to relocate there. As a chef born and raised in South London I understood why it was me he was asking, but for a moment I struggled to come up with an answer. The most enjoyable SW4 dining experiences I could immediately recall were the spicy lamb steamed buns at family-run BYOB joint Dumplings & Baos, or curry goat buss up shut at the bustling Trinidadian takeaway Tawa Roti. However, I had a gut feeling that my friend - a sophisticated type working in wealth management - had something a bit different in mind. “Well, obviously there’s Trinity” - was my eventual reply.

From its opening in 2006, Trinity gained a reputation for rivalling Wandsworth’s Chez Bruce (the only Michelin-starred restaurant in South London at the time) for elegantly executed French-inflected dishes. Chef patron Adam Byatt had already burst onto the Clapham scene a few years earlier with his short-lived restaurant Thyme, notably a vanguard of the ‘small-plates concept’. Jay Rayner’s glowing 2002 review marvelled at the then-novelty of such a way of ordering:

“The idea is that you do away with the standard 'starter/main-course' plan and instead order three or even four of these savoury dishes, each of which is roughly the size of a starter. It immediately appealed to me.”

Alas, Thyme was too ahead of its time and Trinity’s return to a more classic style of menu saw Byatt able to carefully build the restaurant up to Michelin-star recognition, an accolade it still holds.

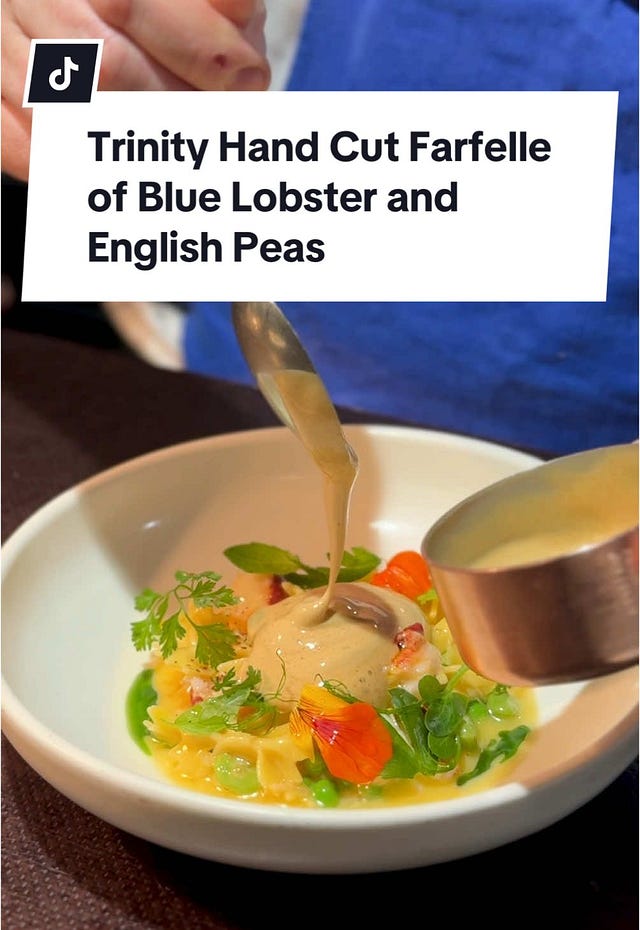

For many years since, Trinity has been a confidently quiet player in the elite restaurant scene - not the typical hyped-up choice for a wealthy food tourist swinging by London but certainly frequented by a dedicated following of local foodie regulars. I was surprised then to see a massive uptick recently in their social media activity, seemingly driven by a partnership forged between Byatt and PR firm Samphire Comms. Along with increased collaborations with podcasts and Topjaw, this new initiative has seen Trinity’s socials populated with well-produced videos of dishes being plated by cooks speaking in an apparently obligatory cheffy vernacular where every single ingredient must be prefixed by “lovely” or “beautiful”.

I was particularly struck by an Instagram press release for their 2025 opening of ‘Trinity Outside’ - a seasonal extension of the main restaurant that makes use of their ample pavement space within the semi-pedestrianised Clapham Old Town. The post’s copywriting promised “bold flavours” as part of a “disruptive” concept, and I was immediately reminded of a radio interview with Jennifer Saenz - Chief Marketing Officer of Doritos parent company Frito-Lay - in which she had memorably remarked:

“With Doritos, it’s a really bold brand. The product itself is bold… bold crunch, bold flavour. And the consumers who are drawn to Doritos… are typically fairly bold in their action and their beliefs and the way they live and the interests that they have.”

Equally, the slogan you are met with when you go to the Doritos website’s About Us page reads:

“Doritos isn’t just a chip - it’s fuel for disruption”.

Whilst it seems bizarre to use such hyperbolic and presumptuous language to describe a corn-based snack, there is strong research-based theory behind the ascription of strong personality traits to consumers. In the same interview, Saenz notes that, rather than trying to appeal to specific demographics with their marketing of Doritos:

“We try to think about the psychographics.”

While demographics give corporations a good picture of who is buying their product, psychographics show why people are buying certain product types - and research shows that it tends to be driven by either actual or aspirational personality traits that consumers associates with themselves. Assuming that your average Doritos consumer or Clapham resident is not living their life in a particularly “disruptive” way, it would seem that the kind of psychographic being targeted by Doritos and Trinity is the aspirational kind.

We might then ask why there exists a large psychographic of consumers who aspire to such bold and disruptive tendencies - and why they are expressing this through their consumption. Doritos certainly appeals to the expressive powers of eating their product, with another Frito-Lay marketing agent stating in an interview that “Doritos is a beacon for self-expression”. This kind of language is not just limited to Doritos of course, with many modern-day advertisements selling self-expression, particularly in response to an increasingly corporatised and culturally flattened world. An advertising poster currently on the platform of Clapham North tube station promises that for those wearing the company’s clothes “typing =SUM never looked so good”, implicitly offering spreadsheet-wrangling commuters the ability to transcend the repressive drudgery of their office job.

The anthropologist David Graeber touched on this idea in his 2013 essay On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs: A Work Rant. In forming his argument, he notes that, from the perspective of some economists at the beginning of the 20th century, it was a foregone conclusion that the work week would keep shrinking in line with technological advances. Eventually the productivity gains produced by new tech would allow the desired standard of living to be achieved with just a 15-hour work week. While undoubtedly huge advancements have been made just as these economists predicted, a concomitant rise in consumption habits has meant that just as much work is still required in order to fuel this newly increased demand.

“Instead, technology has been marshaled, if anything, to figure out ways to make us all work more. In order to achieve this, jobs have had to be created that are, effectively, pointless. Huge swathes of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed.”

Graeber notes that the most productive tasks in society have been automated over the last 100 years, while “professional, managerial, clerical, sales, and service worker” jobs have tripled. He theorises that a lot of these jobs are effectively “bullshit” jobs made up to keep people earning and consuming, which in turn feed other bullshit jobs that provide goods and services to consume. To illustrate this symbiosis we can imagine consultants staying late at the office and then paying Uber Eats to deliver them dinner - then Uber Eats hiring consultants themselves to advise them on how to better exploit the ‘consultants working late’ market. The consequence of this, Graber claims, is that “rather than allowing a massive reduction of working hours to free the world's population to pursue their own projects, pleasures, visions, and ideas”, we see the “unprecedented expansion” of administrative and service industry jobs.

This appears to me to create a tension in which the human yearning to passionately pursue one’s interests is often cruelly restrained by the pursuit of consumption. The modern marketing strategy of Doritos, Trinity and others therefore seeks to resolve this tension by convincing consumers that through their choice to buy the business’ products they are in fact expressing their true selves - apparently disrupting norms by pursuing their own self-directed bold action. This has a soothing effect on consumers, now believing that their “bullshit” job provides a roundabout means of pursuing their own deeply personal visions and convictions, rather than just servicing meaningless consumption. Census data for Clapham shows that 65.8% of residents over-16 are employed in “managerial, administrative and professional occupations”, double the 33% employed in such roles across the whole of England and Wales. Whilst this phenomenon is widespread across the West, such a high “bullshit” job density gives Clapham and neighbourhoods like it a strong appetite for this safely hypothetical disruption, allowing this new wave of advertising to be particularly effective.

It’s hard to know how to navigate this bold new world. Ultimately I advised my friend to go and eat at Trinity. It’s an excellent restaurant with exceptional food and I do think he’ll love it. But as Graeber’s essay flashed across my mind, I quickly added “Tawa Roti’s worth a look too, though”. My friend didn’t look convinced but I hoped he would remember the recommendation. Maybe walking home from the tube after a particularly long day at the office, he’ll find himself drawn to the comforting smells and cheerful chatter emanating from inside. And perhaps he’ll find himself on one of their stools with some curry goat, looking out the window onto the high street and pondering what really matters.

Your writing is phenomenal!!!

Nice! That last bit reminds me of that Ivan orkin epiphany moment sharing ramen with the suits late at night